“In Memory of Mukura Victims,” Daily Monitor, 11 July 2010

http://www.monitor.co.ug/Magazines/-/689844/955242/-/np3613/-/index.html

By Lino Owor Ogora

When Finance Minister Syda Bumba read out the 2010/11 national budget on June 10, she announced that Shs200 million had been set aside for families of the victims of the 1989 Mukura massacre in Teso. The government should be applauded for realising that victims deserve some honour in the form of compensation.

However, this announcement calls for careful planning by all stakeholders, as this new compensation initiative appears to have several flaws, such as lack of victim consultation and the absence of a holistic plan that caters for community reconciliation and justice. These failings could lead to long-term consequences for the victims in Mukura and could establish a dangerous precedent for future reparations policies

The village of Mukura is located in Kumi District. According to a witness who was present at the time of the massacre, “On July 11, 1989, the 106th Battalion of the NRA (former name of the national army) rounded-up 300 men suspected of being rebel collaborators against the NRA regime and incarcerated them in a train wagon.”

Little evidence

There is little evidence to suggest that most of these men were anything other than innocent civilians. Trapped in the crowded train wagon, trying not to trample on one another, the men struggled to breathe, and by the time they were released after more than eight hours, 87 had suffocated to death. (This figure and some other details are highly contested, showing the need for a credible truth-seeking process into the event). The dead were hastily interred in a makeshift mass grave but their remains were later exhumed and re-buried in a memorial mass grave constructed by the government.

Our witness testified that President Museveni visited Mukura in October 1989 and promised a compensation of Shs2 million for each deceased person. In December 1989, Shs800,000 out of the Shs2 million was paid out to the families of all the 87 deceased men as a partial payment. This money was to be used by the recipient to buy a bicycle, an ox-plough and a pair of oxen. Since then, the victims have waited for the balance of Shs1.2 million; it did not show any signs of materialising until the recent announcement by finance minister. This move, positive as it may be, falls short in several ways

Questions remain

First, according to recent interviews held with civil society in Mukura, the government has not meaningfully consulted with the victims about their needs and the form that reparations should take. Several questions remain unanswered. How was the figure of Shs200 million derived? Is it a fulfilment of the long-awaited balance which was promised in 1989? When we visited Kumi town on June 21, our inquiries of government and civil society failed to produce any definitive answers, and the victims’ families continue to remain in the dark. The government needs to shed light on this.

Secondly, it is not known whether the new initiative will holistically address the range of needs of victims of mass atrocities. While different communities might require different processes, commonly-accepted transitional justice measures include accountability for perpetrators, truth seeking, reconciliation and memorials. Specifically: Truth-seeking and accountability: What has become of the commanders in charge of the 106th battalion that perpetrated the massacre?

Were they acting on their own initiative or based on ‘orders from above’? If so, then who is the most responsible in the chain of command?

It is alleged that a commission of inquiry was set up by the President in 1989, but its findings were never published. Furthermore, acknowledgement of the massacre should be accompanied with accountability.

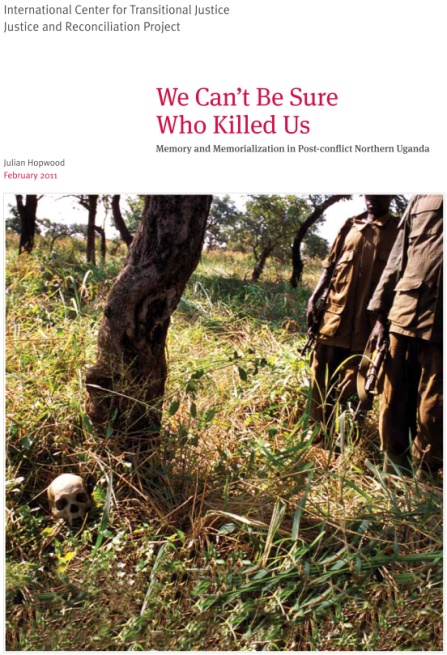

Memorialisation: The government has already constructed a memorial secondary school in Mukura and a memorial mass grave at Okunguro Railway Station where the remains of the victims were buried. This memorial lacks connectedness to the victims and their families, and has fallen into a state of disrepair, having been overrun by natural vegetation and ants.

No consultations

Furthermore a building which was reportedly supposed to house a public library lies incomplete. Victims and community members should be consulted to see if the memorials should be refurbished, or different memorials created.

Thirdly, it is also important to make sure that reparations are not used as a political gambit. Because the compensation for Mukura survivors was announced in the run-up to the 2011 elections, skeptics have begun to doubt the governing party’s motives.

Unless the government pronounces itself on this issue, this seemingly good cause may be interpreted as an attempt to silence the victims and ‘buy’ their votes ahead of the 2011 elections.

It is therefore incumbent upon government to make the Mukura question a success, so that the results set a blueprint for the much needed policy on reparations in Uganda.

This lesson could help the case of northern Uganda where it is claimed that the office of the presidential advisor on northern Uganda has been actively engaged in registering victims for future reparations.

What criteria

This would go a long way in answering the question of, ‘what criteria should be used to register victims, and also provide insights on what a reparations policy should consider’. These questions, plus many others would also be useful in the case of Luweero Triangle and Western Uganda, where the government is also planning to make reparations.

There is need for coordination of all these efforts to ensure that reparations schemes across the country are consistent. There is also a need to consult with victims before any definite decisions are reached in order to fully involve them in the process.

Mr Ogora is team leader, Research and Advocacy, Justice and

Reconciliation Project, Gulu