“The End of Amnesty: Whither “Peace Versus Justice” in Northern Uganda?” Justice in Conflict blog, 12 June 2012

http://justiceinconflict.org/2012/06/12/the-end-of-amnesty-whither-peace-versus-justice-in-northern-uganda/

By Mark Kersten

I couldn’t resist contributing to the discussion that Mark Schenkel has begun with his fantastic post on the expiration of northern Uganda’s Amnesty Act. Readers shouldn’t let the fact that the story hasn’t been widely covered fool them into believing it isn’t of tremendous importance or that its implications aren’t significant. As Mark has shown, it is and they are.

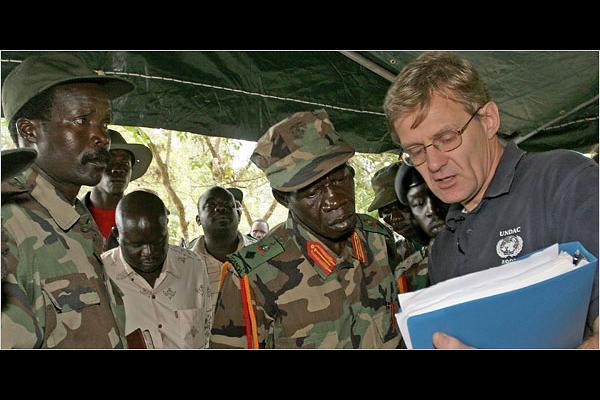

I wanted to highlight just how remarkable it is that not only has the expiration of Part 2 of the Amnesty Act come as a surprise to many observers, but it has subsequently been met with barely a murmur – almost as if it wasn’t all that important. This is noteworthy in its own right. When the ICC intervened in northern Uganda in 2004 and subsequently issued arrest warrants for LRA leader Joseph Kony and four other senior rebel commanders, the “peace versus justice” floodgates opened. The debate was pervasive and polarizing. Much of it revolved around the over-simplified but potent question of whether rebels should be forgiven via amnesty or punished via the ICC. A legion of local and international voices declared that peace could only be achieved if LRA rebels could be guaranteed that they would not be prosecuted if they left the bush. This view was premised on fears that the threat of prosecuting rebels would leave them with no option but to continue fighting. They consequently called on the ICC to back off and give peace through forgiveness a chance. Of course, the ICC warrants stayed in place. However, thousands of LRA combatants received amnesty certificates following their defection from the rebel ranks.

Just years later, the “peace versus justice” debate has virtually disappeared. Take, for example, the prosecution of Thomas Kwoyelo, the former senior LRA commander who was detained by the Ugandan forces (UPDF) in 2009. True, the controversy around Kwoyelo’s prosecution has concerned whether he should be issued an amnesty. But the debate has almost exclusively been a legal debate, centering around whether or not he is eligible to receive an amnesty under Ugandan law (answer: absolutely) and whether receiving an amnesty is in contravention of Uganda’s international obligations (answer: I don’t think so). What the debate hasn’t been about is whether granting Kwoyelo amnesty would risk undermining the progress northern Uganda has made towards order and stability.

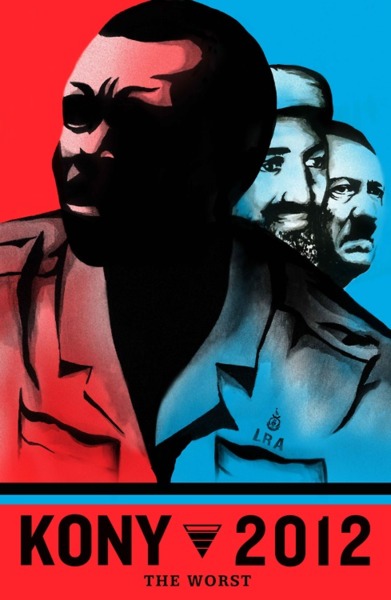

Consider too the example of Caesar Achellam, the LRA rebel commander who was recently “captured” by Ugandan military forces. Again, there exists no palpable concern that arresting Achellam and possibly putting him on trial jeopardizes peace in northern Uganda. Interestingly, the Achellam story has received significantly more international coverage than the Kwoyelo trial. But it received attention primarily because of Invisible Children’s ‘KONY2012′ campaign. As I noted previously, virtually every story about Achellam’s “capture” cited KONY2012 and the now world-famous “hunt for Joseph Kony”.

Moreover, in my experience interviewing individuals involved in the northern Ugandan peace process, including government ministers, religious and civil society leaders, as well as delegates from the peace talks, there remains almost little to no concern that the ICC or any form of trial justice risks undermining peace. In short, it really does appear that northern Uganda has moved beyond the “peace versus justice” debate.

To those who study the region, this will come as little surprise. Northern Uganda is currently enjoying the longest period of ‘negative peace’, or what many call a “silence of the guns”, in decades. During and following the Juba Peace Talks (2006-2008) the LRA, and the conflict between the LRA and the Government of Uganda more generally, was exported out of northern Uganda to the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Central African Republic and Sudan. Sure, the LRA had been operating in these areas long before the Juba negotiations, but no large-scale LRA attacks have occurred in northern Uganda since the talks began. Today, it is not fear of LRA offensives or abductions that dominate public discourse in northern Uganda. Instead, it is critical issues such as nodding disease, low education standards and land grabs.

I find this development particularly interesting as it fits within the context of the history of ‘transitional justice’. Other states too have only sought trial justice after a period of impunity when amnesties were granted to perpetrators. I have previously argued (see here and here) the record suggests that it is only when fear that prosecution will destabilize or undermine a transition to peace dissipates that societies stop opposing prosecutions.

Of course, this does not mean that a policy recommendation for transitional states should be to issue amnesties and then to revoke them when they’re good and ready. In the northern Ugandan case, no amnesties will be revoked; amnesty certificates simply won’t be issued any longer. More importantly, sequencing peace and justice through the use of amnesties may be a fallacy – no combatant or perpetrator would ever trust the use of amnesties that they knew would subsequently expire or be revoked.

None of this is to say that there is no longer any reason to continue granting amnesties. Some continue to believe amnesty remains an integral ingredient in helping to promote peace in northern Ugandan – and they might be right. For example, Michael Poffenberger, of Resolve, recently argued that the Amnesty Act can still play an important role in diminishing the LRA as a rebel force.

Moreover, the expiry of the amnesty was clearly done without much concern for the democratic process. The issue wasn’t discussed in Uganda’s Parliament. Troublingly, local citizens and groups weren’t properly or sufficiently consulted. The opinion in northern Uganda, as assessed by Justice and Reconciliation Project, clearly indicates a majority support for the continuation of the Act.

There remains a desperate need for a comprehensive and cohesive transitional justice strategy in Uganda. Amnesties for low-level LRA rebels outside of northern Uganda should probably be included. But it remains remarkable just how far northern Uganda has come since the days when the “peace versus justice” debate dominated the headlines. It is increasingly unfeasible to argue that unless the Amnesty Act is continued, the very peace that northern Uganda enjoys is itself at risk. In other words, the very boundaries of the amnesty debate have changed. Amnesty or not, the people of northern Uganda will continue on their path towards peace and justice.