(Oryem Nyeko) Hello and welcome to the second episode of JRPs’ podcast. I am Oryem Nyeko, I am with my colleague Okwir Isaac Odiya of JRP to talk about a report title ‘ Mapping Regional Reconciliation In Northern Uganda: A Case Study Of Acholi And Lango Sub- Region.

(Okwir Isaac Odiya) Across Ethnic Boundaries project came from the background of our interactions with the community of Acholi, Lango, Teso and West Nile which we learned about the poor relationship and the accusations that is within these communities. We thought of doing this regional reconciliation project to understand whether there is need for regional reconciliation in northern Uganda. This made us to do a baseline study which we came out with the result. This baseline study or the regional reconciliation survey that we did was meant to provide us a baseline for peace building and reconciliation undertaking in northern Uganda. Basically to inform us whether it is true that there is need for reconciliation between the people of northern Uganda and what mechanism therefore should be adopted in order to foster reconciliation in Northern Uganda.

(Oryem) So the baseline is reported in this report that we are talking about…

(Isaac) Exactly, the ‘Mapping of Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda’ is the result of the baseline survey that we did.

(Oryem) So what are some of the findings in the report? What did you find out about the need for regional reconciliation?

(Isaac) From the report, we came with key findings and one of it is the negative perception about the civil war – the war that was fought between the government of Uganda and the LRA. We realized that many people perceived the war as a war that was planned by one ethnic group against the other which basically in many communities that we interacted with, they claim that it was an Acholi war made to make other ethnic groups suffer. So that is one of the findings we realized on the ground.

The second finding is about the tension which is among the ethnic groups in northern Uganda as a result of the crimes that were committed among these communities. There is interpersonal community and ethnic tension which basically people think they were made to suffer because of some other individuals, because of some other community or because of some other ethnic groups.

From the survey that was conducted, we noted that 62% says that there is poor relationship among the people of Lango and Acholi which is as a result of LRA war. They feel that the people of Acholi planned to kill the people of Lango so because of this, there is that poor relationship between the people of Acholi and the people of Lango.

We also noted that in the communities or among the different communities there is fear of revenge by other communities because of what they did maybe. In some of the communities there are some individuals that were involved in some of the atrocities and because of what they did in the atrocities that they feel that their counterparts are going to revenge on them. So there is that fear of revenge within the communities. So generally there is that accusations among the communities, they claim that they suffered because of that individual or that community.

We also found that the community and the individuals are so bitter for lack of accountability and reparation programme. Many individuals and many communities were made to suffer but there is no acknowledgement of the crimes committed on them, there is no accountability for what they underwent and there is no programme to repair them. So the communities are so bitter on the government, they are so bitter on their leaders, they are so bitter on each other within the community because they feel they are not being repaired, they are not being acknowledged for the wrongs that happened to them. Generally the communities feel that they are being segregated in post-conflict service provision. There are a number of programmes that are enrolled by civil society organisations, by the local government but they feel that the services are balanced. It’s not reaching them all, it’s only being directed to one section of the community. Because of this they feel that there is segregation in provision of these services that should really help them to come out of the problem they went through to repair them, to recover from the shock of the war. And because of this segregation, they feel that they are not being honored, they are not being acknowledged as people who also suffered.

In our own analysis we feel that this is another potential source of conflict in that if they feel that one section of the community is being supported to recover from the problem, it means they are not being supported and easily they can begin to revenge, they can begin to cause another conflict on the government or on the communities that are benefiting from some of these services.

(Oryem) I’m curious, what do you think are some of the root causes of what you are talking about – the segregation; some communities not receiving the programmes that are meant to address the legacy of the war. What’s the cause of that, do you think?

(Isaac) I think there is lack of a baseline study to understand the different needs of the communities and what they went through. Our service providers – it looks like they don’t understand our communities, what they went through and the kind of services they need so they are kind of neglecting some of these communities to benefit from some of these services. To me I feel that they are not informed, they don’t know what services are supposed to be provided for which communities, which is a gap and that is the only gap I feel.

But also, it is important that we need to train our service providers to know how to work with the victims of conflict. In a way we may also be causing conflict by failing to understand the circumstances that our communities went through. Like when we were interacting with this communities, the people of Odek made mention about the kind of segregation that they are going through. We were made to know that the people of Odek are being considered as Kony, in that they have supported Kony, they groomed Kony to be what he is and Kong is now affecting. So they contributed in making Kony who he is, and because of that they are being treated as Kony. So I feel that the service providers should be able to separate the people of Odek and Kony himself, taking the fact that they also suffered a lot in the hand of Kony.

(Oryem) So what needs to be done? I mean, you’ve elaborated a bit on that with service providers maybe needing to be more informed about the needs and experiences of the various communities, but what’s a next step in terms of reconciling some of these issues?

(Isaac) In line with service provision, that is basically one of the reasons why we did this report. We want this report to inform transitional justice processes in Uganda and in northern Uganda. We want these key findings and recommendations in this report, Mapping Regional Reconciliation, to really inform the different stakeholders – peacebuilders and reconciliation activists to really know what are the gaps in the community and then what are some of the steps that are required to be taken in order to mitigate or to provide remedies to some of these gaps in the community. So that is the first step.

I would urge the different stakeholders to really pay attention to this report so that they can learn the kind of community we are working with, the gaps in the community and the kind of careful steps they should take in order to provide reconciliation within these communities.

Secondly, it is important to work in partnership, the different civil society organizations, the NGOs and the government, the local government. We need to be coordinating so that we inform each other on the gaps on the ground and then the best step, we can brainstorm on the best steps that should really be taken so that we really reach this community so that we address the specific gaps in this community. And by doing this we are going to act in the interests of the community we are serving.

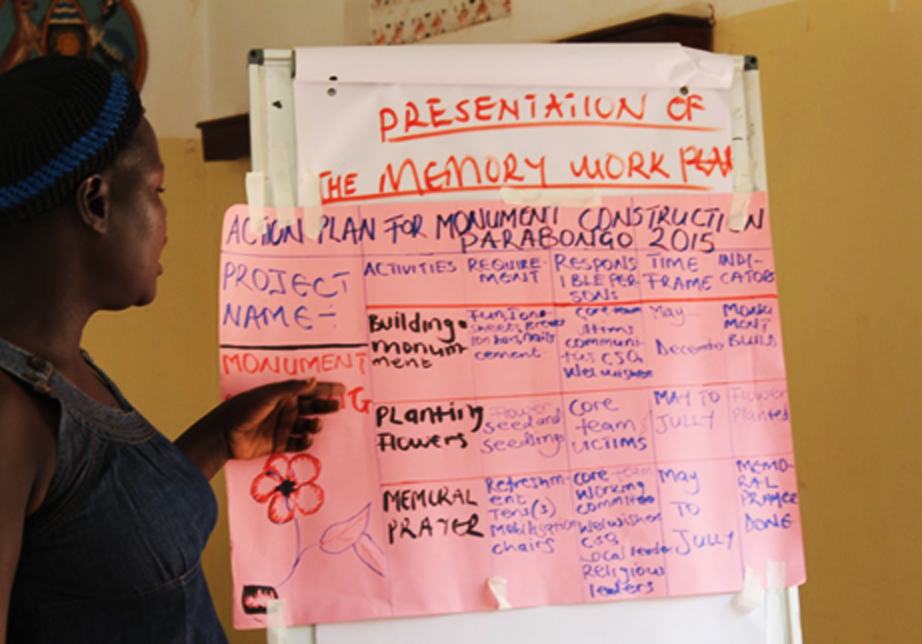

I want to mention another few things in regards to reconciliation gaps. What requires to be done. We also noted that there is a lack of platform to foster reconciliation, in that victims’ communities are there in the community, but they lack forums to which they should really communicate, to which they should really engage to address some of their own problems. This is also coupled with the criminal prosecution process that is going on, the trial of Kwoyelo, the trial of Dominic Ongwen, which is kind of fueling more conflict in the community. So there is also this problem that is existing in the community following the survey that we conducted, or working with these communities. Which my recommendation would go to the various stakeholders to really support the peacebuilding and reconciliation structures that we have on the ground or to establish more, so that they provide pillars to these conflict affected community to interact with, to discuss their issues, to support them in their reconciliation and recovery programme.

It’s all about providing a platform for these people to interact, to really try to see the best way of addressing some of their issues, to channel their problems so that it is heard and addressed by the stakeholders.

I would also recommend for a trauma healing project to really be enrolled in the community so that people find ways to move out of their problems instead of getting stuck. Much as accountability has not been done, much as there is no adequate reparation they still need to move on with their lives. So it is important to have such programmes.

(Oryem) Can I just ask how do the criminal proceedings fuel conflict in these communities?

(Isaac) From the interaction we had with these communities, we learned that they have varying interests in line with the result of the verdict. In the case of Dominic Ongwen’s trial, there are those who want to see Dominic Ongwen prosecuted, they want to see him guilty and there are those who want to see Dominic Ongwen coming back home acquitted from the sentence.

So you can see the communities are now looking at those who are in support of Dominic Ongwen as those who supported the atrocities that made them suffer in northern Uganda. Those who look at the people who want to see Dominick Ongwen jailed, they look at them as those who do not want reconciliation to be done so that people get to live back together.

(Oryem) Because of course the question of criminal accountability and Dominic Ongwen has implications on the communities that have been affected by the case for Lukodi, I imagine that’s what you’re talking about, and the other communities, Odek, Abok, and so on, that his charges are based on, they obviously have a vested interest in seeing some sort of accountability towards him. Whereas in other communities, in Coorom, for example, where Ongwen is from there is a sense that there should be more of a reconciliatory process. Although in my experience, I found that even people in Lukodi also want to reconcile with the people from where Ongwen is from, which I find interesting and I think it kind of speaks to the point that you’re making that these issues have a regional aspect to them. In that it’s not the same everywhere. Not everyone in northern Uganda has the same sense, not everyone in Acholi and Lango has the same feelings towards Ongwen or to criminal accountability or to the impact of the war. I think that’s kind of it

(Isaac) Exactly, and that’s where it calls for how do we manage the process? So that at the end of it all, irrespective of the result of the trial, how are we going to ensure that there is reconciliation, how are we going to we to work together, the people of Lango, the people of Acholi, the people of Lukodi, the people of Coorom, irrespective of the results of the hearing. This is what we should manage.